Ionic Compound Names and Formulas Made Easy

Understanding Ionic Compound Names and Formulas

Ionic compounds are formed when one or more electrons are transferred between atoms, resulting in the formation of ions with opposite charges. The electrostatic attraction between these oppositely charged ions holds them together, creating a strong chemical bond. In this article, we will explore the world of ionic compound names and formulas, making it easy for you to understand and work with them.

What Are Ionic Compounds?

Ionic compounds are composed of cations (positively charged ions) and anions (negatively charged ions). Cations are typically formed when metals lose electrons, while anions are formed when nonmetals gain electrons. The electrostatic attraction between the oppositely charged ions holds them together, forming a strong chemical bond.

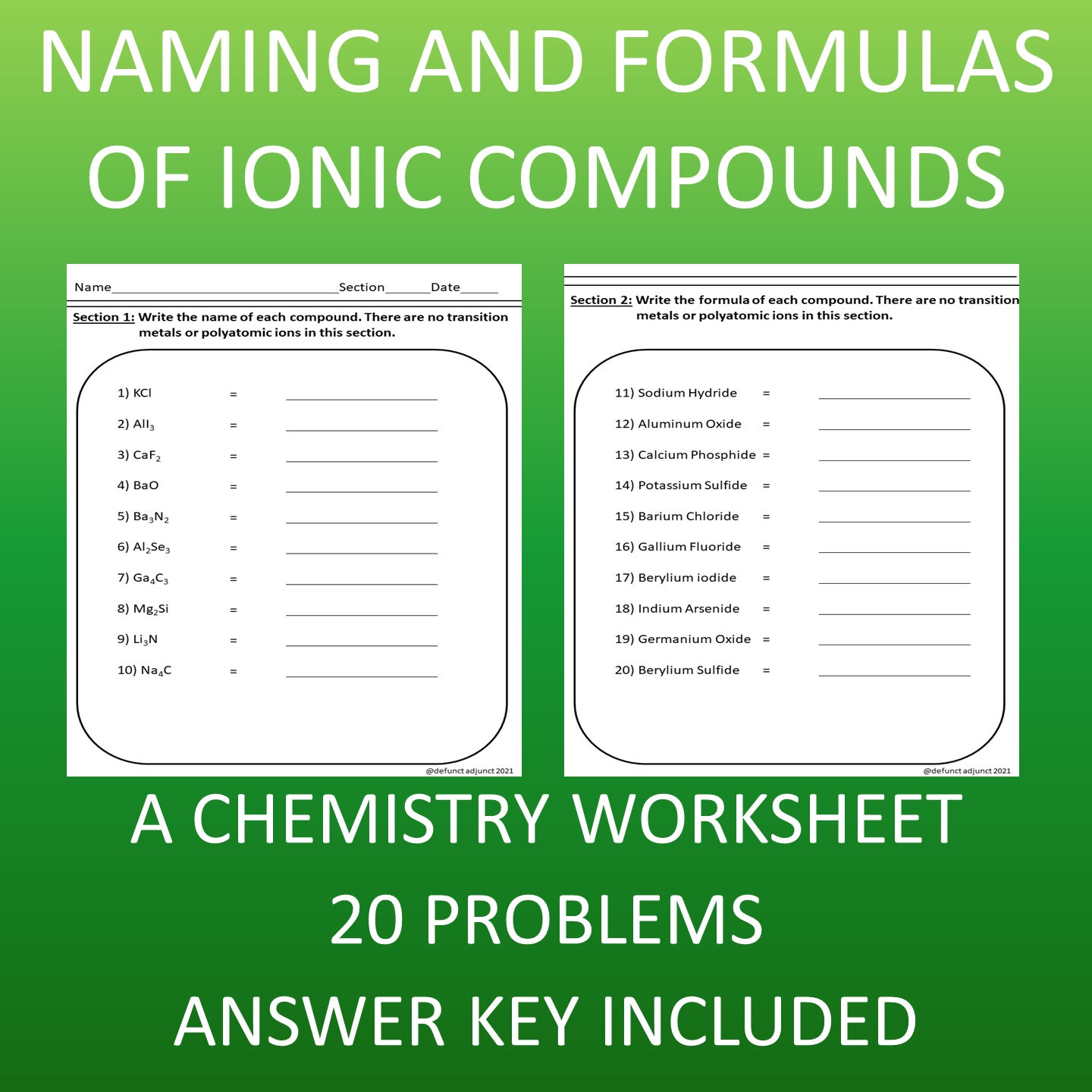

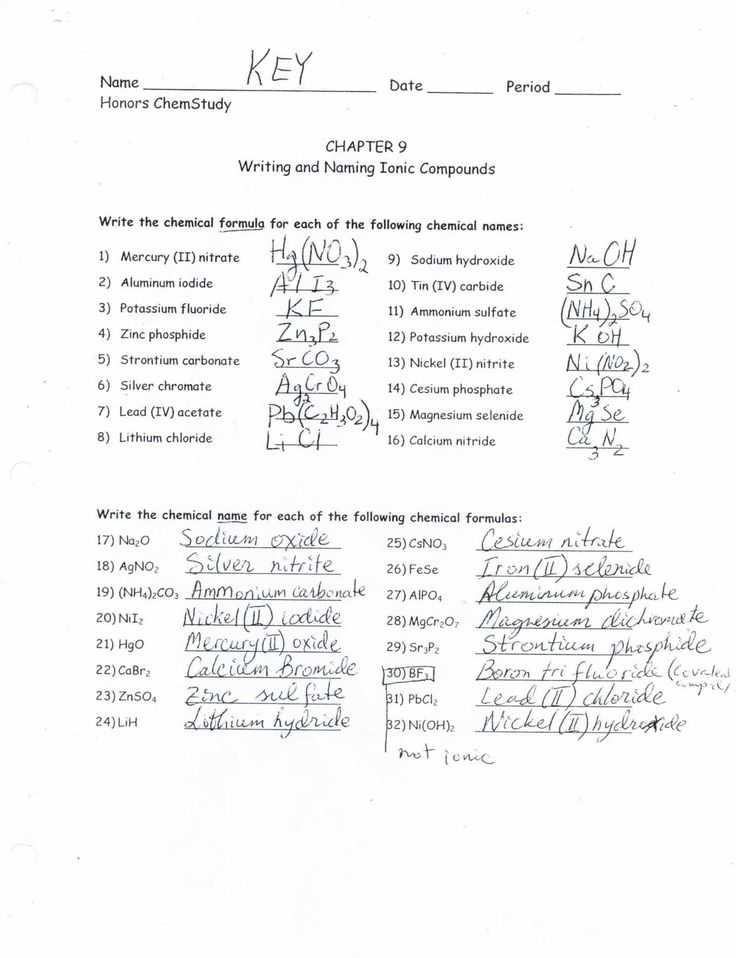

Naming Ionic Compounds

Naming ionic compounds can seem daunting, but it’s actually quite straightforward. Here are the basic rules:

- Cation First: When naming an ionic compound, always start with the cation (positively charged ion).

- Anion Second: After the cation, add the anion (negatively charged ion).

- Use Greek Prefixes: If there are multiple anions, use Greek prefixes to indicate the number of anions. For example, “di” for two, “tri” for three, and so on.

- Drop the Ending: When adding the anion, drop the ending of the element’s name and add the suffix “-ide”.

Here are some examples:

- Sodium chloride (NaCl) - Sodium (cation) + Chloride (anion)

- Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) - Calcium (cation) + Carbonate (anion)

- Iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) - Iron(III) (cation) + Oxide (anion)

Writing Ionic Compound Formulas

Writing ionic compound formulas is just as easy as naming them. Here are the basic rules:

- Cation First: Always start with the cation (positively charged ion).

- Anion Second: After the cation, add the anion (negatively charged ion).

- Balance the Charges: Make sure the total positive charge of the cation equals the total negative charge of the anion.

Here are some examples:

- Sodium chloride (NaCl) - One sodium ion (Na+) and one chloride ion (Cl-)

- Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) - One calcium ion (Ca2+) and three carbonate ions (CO32-)

- Iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) - Two iron(III) ions (Fe3+) and three oxide ions (O2-)

Common Ionic Compounds

Here are some common ionic compounds and their formulas:

| Compound | Formula |

|---|---|

| Sodium chloride | NaCl |

| Calcium carbonate | CaCO3 |

| Iron(III) oxide | Fe2O3 |

| Copper(II) sulfate | CuSO4 |

| Potassium nitrate | KNO3 |

Transition Metal Ions

Transition metal ions are a special case. They can have multiple charges, depending on the number of electrons lost. To indicate the charge of a transition metal ion, we use Roman numerals in parentheses.

Here are some examples:

- Iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) - Iron(III) ion has a charge of +3

- Copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4) - Copper(II) ion has a charge of +2

- Chromium(III) chloride (CrCl3) - Chromium(III) ion has a charge of +3

💡 Note: When writing the formula for a transition metal ion, make sure to indicate the charge using Roman numerals in parentheses.

Conclusion

Naming and writing ionic compound formulas can seem daunting at first, but with a little practice, you’ll become a pro in no time. Remember to always start with the cation, followed by the anion, and balance the charges. With these simple rules, you’ll be able to tackle even the most complex ionic compounds with ease.

What is the difference between a cation and an anion?

+

A cation is a positively charged ion, typically formed when a metal loses electrons. An anion is a negatively charged ion, typically formed when a nonmetal gains electrons.

How do I determine the charge of a transition metal ion?

+

The charge of a transition metal ion is determined by the number of electrons lost. We use Roman numerals in parentheses to indicate the charge, such as iron(III) or copper(II).

What is the purpose of using Greek prefixes in ionic compound names?

+

We use Greek prefixes to indicate the number of anions in an ionic compound. For example, “di” for two, “tri” for three, and so on.